Electric charge and electric current are the two of the most fundamental quantities in electrical engineering and applied physics. Without these two concepts, modern electronics and power systems would not exist. Every circuit you design, every motor you study, and every electronic device you use works because of electric charge and current. Electric charge, measured in Coulombs (C), is a scalar quantity that describes the electromagnetic property of subatomic particles. Electric current, measured in Amperes (A), quantifies the rate of charge flow through a conductive medium per unit time.

This technical guide covers the theoretical foundations of electric charge and current along with their mathematical formulations, physical interpretations, and engineering applications.

1. What is Electric Charge?

Electric charge is a basic property of matter. It is the reason why certain particles attract or repel each other. The concept of charge comes from observations made centuries ago when scientists noticed that rubbing certain materials together caused them to attract lightweight objects.

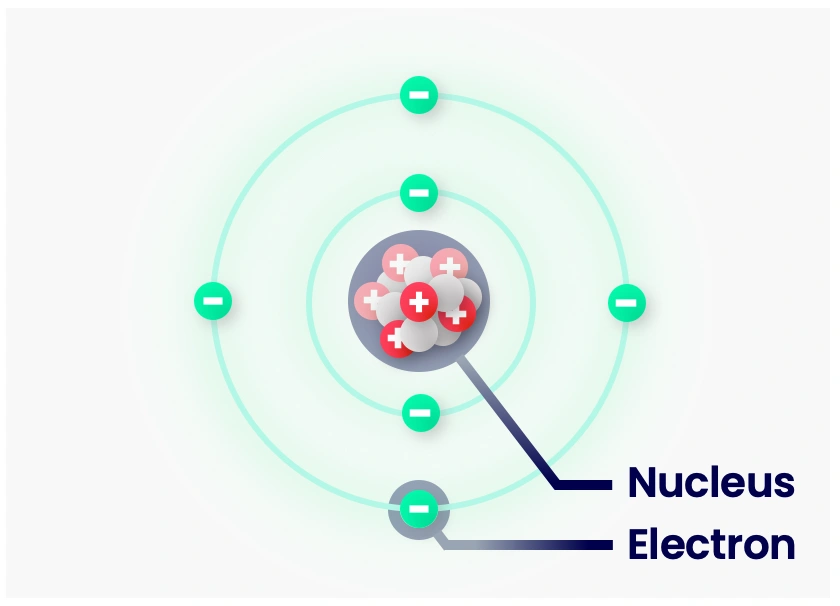

At the atomic level, charge exists in two forms. Protons carry positive charge while electrons carry negative charge. Neutrons have no charge at all. When an object has more electrons than protons, it becomes negatively charged. When it has more protons than electrons, it becomes positively charged.

The unit of electric charge is the Coulomb, named after French physicist Charles-Augustin de Coulomb. One Coulomb equals the charge of approximately 6.242 × 10^18 electrons. This is a very large number, which shows just how tiny the charge of a single electron really is.

1.1 Example of Electric Charge in Daily Life

When you rub a balloon against your hair, electrons transfer from your hair to the balloon. The balloon gains extra electrons and becomes negatively charged. Your hair loses electrons and becomes positively charged. This is why your hair stands up and gets attracted toward the balloon.

1.2 Properties of Electric Charge

Electric charge has several properties that every engineering student must learn. These properties explain how charges behave in different situations.

1.2.1 Quantization of Charge

Charge always exists in discrete packets. You cannot have a fraction of an electron’s charge. The smallest unit of charge is the charge of one electron (or proton), which equals 1.6 × 10^-19 Coulombs. Any charge you measure will always be a multiple of this value.

Mathematically, any charge Q can be expressed as:

\(Q=ne\)

where \(n\) is any integer (positive, negative, or zero) and \(e\) is the elementary charge. This means charges of \(1e,\,2e,\,3e,\,-5e,\) etc., can exist, but fractional charges like \(0.5e\) or \(3.7e\) cannot occur in ordinary matter.

For example, if you have a charge of 3.2 × 10^-19 Coulombs, this equals the charge of exactly two electrons. You will never find a charge of 2.4 × 10^-19 Coulombs in nature because that would require 1.5 electrons, which is impossible.

1.2.2 Conservation of Charge

Charge cannot be created or destroyed. It can only be transferred from one object to another. The total charge in an isolated system remains constant.

When you charge a plastic rod by rubbing it with cloth, the rod gains electrons that the cloth loses. The total charge of the rod and cloth together remains zero. This principle is called the conservation of charge.

1.2.3 Additive Nature of Charge

Charges add up algebraically. If you have +5 Coulombs and -3 Coulombs together, the net charge is +2 Coulombs. This additive property makes calculations straightforward in circuit analysis.

The additivity property states that if a system contains multiple charges \(q_1,\,q_2,\,q_3,………,q_n\), the total charge \(Q\) is simply their algebraic sum:

\(Q=q_1+q_2+q_3+……+q_n\)

1.3 Types of Electric Charge

There are only two types of electric charge: positive and negative.

Positive Charge: Protons carry positive charge. When an object loses electrons, it becomes positively charged. The symbol for positive charge is (+).

Negative Charge: Electrons carry negative charge. When an object gains extra electrons, it becomes negatively charged. The symbol for negative charge is (-).

1.4 Interaction Between Charges: Coulomb’s Law

Like charges repel each other. Two positive charges push each other away. Two negative charges also push each other away. Unlike charges attract each other. A positive charge pulls a negative charge toward it.

This interaction follows Coulomb’s Law, which states that the force between two charges is directly proportional to the product of their magnitudes and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Mathematically, Coulomb’s Law is expressed as:

\(F=k\frac{q_1 q_2}{r^2}\)

Where:

- F = Force between charges (in Newtons)

- k = Coulomb’s constant (8.99 × 10^9 N·m²/C²)

- q₁ and q₂ = Magnitudes of charges (in Coulombs)

- r = Distance between charges (in meters)

1.5 Conductors and Insulators

Materials respond very differently to the presence of electric charges. This leads to their classification as either conductors or insulators.

Conductors are materials containing free electrons that can move easily throughout the material. Metals such as copper, aluminum, silver, and gold are excellent conductors due to their atomic structure that features one or two loosely bound electrons in the outermost shell. These electrons are not tightly bound to individual atoms and can drift through the material in response to an applied electric field.

In contrast, insulators are materials in which electrons are tightly bound to their atoms and cannot move freely. Materials like rubber, plastic, glass, and wood serve as good insulators. When charge is added to an insulator, it tends to remain localized at the point of application rather than spreading throughout the material.

2. What is Electric Current?

Electric current is the flow of electric charge through a conductor. When charges move in an organized manner through a material, we say current is flowing. Current is not just the presence of charge. It is specifically the movement of charge.

Think of electric current like water flowing through a pipe. The water molecules represent charges. When they move through the pipe, we have flow. Similarly, when electrons move through a wire, we have electric current.

If an amount of charge \(Q\) passes through a cross-section of a conductor during a time interval \(t\), the current \(I\) is defined as:

\(I=\frac{Q}{t}\)

Where:

- I = Current (in Amperes)

- Q = Charge (in Coulombs)

- t = Time (in seconds)

Equivalently, current represents the rate of change of charge with respect to time:

\(I=\frac{dQ}{dt}\)

The unit of electric current is the Ampere (A), named after French physicist André-Marie Ampère. One Ampere means one Coulomb of charge flows through a cross-section of a conductor every second. To put this in perspective, one ampere represents approximately \(6.242\times 10^18\) electrons flowing past a point every second.

2.1 Example Calculation

If 15 Coulombs of charge flow through a wire in 3 seconds, what is the current?

I = Q / t

I = 15 / 3

I = 5 Amperes

This means 5 Coulombs of charge pass through any cross-section of the wire every second.

2.2 Conventional Current vs. Electron Flow

The direction of conventional current and the actual movement of electrons are not the same. This difference has historical roots. Early scientists assumed that current consisted of positive charges flowing from the positive terminal to the negative terminal of a battery. They made this assumption before anyone knew electrons existed. At that time, no one understood what actually carried electrical charge through wires.

We now know that electrons are the real charge carriers in metallic conductors. These electrons carry negative charge and move from the negative terminal toward the positive terminal. In other words, electrons travel in the opposite direction to conventional current. You might wonder why we still use this outdated convention. The answer is practical. Conventional current gives us correct answers in circuit calculations. All the mathematical relationships work out properly regardless of which direction we choose.

2.3 Mechanism of Current Flow in Conductors

Metallic conductors like copper and aluminum have a specific atomic structure. Their atoms arrange themselves in a regular pattern called a crystal lattice. The nuclei and inner electrons stay locked in fixed positions within this lattice. The outermost electrons behave differently. These outer electrons are loosely attached to their parent atoms. They can break free and wander throughout the metal. Scientists often describe these electrons as forming a “sea” of free electrons that fills the spaces between atoms.

When no voltage is applied to a conductor, these free electrons still move. They zip around at enormous speeds due to thermal energy. At room temperature, their velocities reach about 1 million meters per second. However, this motion is completely chaotic. Electrons bounce around in random directions like balls in a lottery machine. One electron moves left while another moves right. The result is zero net movement of charge. No current flows because the random motions cancel each other out.

The situation changes when you connect the conductor to a battery. The battery creates an electric field inside the wire. This field pushes on the free electrons and gives them a preferred direction of travel. Since electrons carry negative charge, they drift toward the positive terminal.

2.4 Drift Velocity

The average speed at which electrons move through a conductor due to an applied voltage is called drift velocity. We represent it with the symbol \(v_d\). This velocity is surprisingly small. In a household copper wire carrying normal current, electrons drift at about 0.0001 meters per second. That means an electron takes roughly 20 minutes to travel just one meter through the wire. Compare this to their thermal speeds of 1 million meters per second. The drift velocity is millions of times slower.

This raises an obvious question. If electrons move so slowly, why do lights turn on instantly when you flip a switch? The answer lies in the electric field. When you close a circuit, the electric field propagates through the wire at nearly the speed of light. This field immediately starts pushing on all the free electrons throughout the entire wire. You do not wait for individual electrons to travel from the switch to the light bulb. The signal travels almost instantaneously even though individual electrons crawl along slowly.

The mathematical relationship between drift velocity and current is expressed as:

\(I=n A v_d q\)

In this equation, \(I\) represents the current in amperes. The symbol \(n\) stands for the number of free electrons per cubic meter of the conductor material. For copper, this value is approximately \(8.5\times 10^{28}\) electrons per cubic meter. The variable \(A\) is the cross-sectional area of the wire. The drift velocity is \(v_d\), and \(q\) is the charge on each electron \((1.6×10^{−19}\) coulombs).

2.5 Current Density

Current density provides a more detailed picture of how current distributes itself within a conductor. While current tells you the total charge flowing through a wire per second, current density tells you how that flow spreads across the wire’s cross-section. We represent current density with the symbol \(J\) and define it as the current flowing through each unit area of a conductor.

The relationship between current density and drift velocity is given by:

\(J=n v_d q\)

Here, \(n\) represents the number of free electrons per cubic meter, \(v_d\) is the drift velocity, and \(q\) is the charge on each electron. You can also express current density as the total current divided by the cross-sectional area:

\(J=\frac{I}{A}\)

The units of current density are amperes per square meter (A/m²).

Current density is a vector quantity. It has both magnitude and direction. The direction of current density points along the path of conventional current flow. In a straight wire, the current density vector points parallel to the wire’s axis.

3. Types of Electric Current

Electric current exists in two main forms. These are direct current and alternating current. Both types have their own characteristics that make them suitable for specific applications. The selection between them depends on several factors. These include how far the power needs to travel, whether energy storage is required, and what kind of devices will use the power.

3.1 Direct Current (DC)

Direct current moves in only one direction. The electrons travel steadily from the negative terminal of a power source through the external circuit. They then return to the positive terminal. This one-way flow never changes its direction. The amount of current may vary over time. However, the direction always remains the same.

3.1.1 Sources of Direct Current

Batteries are the most common source of direct current. Think about what happens when you put batteries into a flashlight. The electrons leave the negative terminal and pass through the light bulb. They then enter the positive terminal. This flow keeps moving in the same direction until the battery loses all its stored chemical energy.

Several other devices also produce direct current. Solar cells convert sunlight into DC electricity. Fuel cells generate DC through chemical reactions. DC generators produce direct current through mechanical rotation. Almost every electronic device around you contains a power supply that changes AC into DC.

3.1.2 Advantages of Direct Current

DC has one major benefit that AC simply cannot offer. You can store it. Batteries store electrical energy and release it as direct current. Capacitors and supercapacitors work the same way. This storage ability makes DC necessary for portable devices. Your laptop, camera, smartphone, and electric vehicle all run on stored DC power.

Hospitals and data centers use backup power systems that store DC energy. When the main power fails, these systems release the stored energy to keep equipment running.

3.1.3 Limitations of Direct Current

DC has drawbacks for long-distance power transmission. Sending DC over hundreds of kilometers creates problems. You need either very high voltages or extremely thick cables. This limitation pushed engineers to adopt alternating current for power distribution networks.

3.2 Alternating Current (AC)

Alternating current changes its direction at regular intervals. The electrons do not flow steadily in one direction like they do in DC. Instead, they move back and forth in an oscillating pattern. Both the amount and direction of current keep changing. This change follows a smooth wave-like pattern called a sinusoidal waveform.

3.2.1 Frequency of Alternating Current

Frequency tells us how many complete cycles happen in one second. A single cycle includes four stages. First, the current flows forward until it reaches maximum strength. Then it decreases to zero. Next, it reverses and flows backward until it reaches maximum in the opposite direction. Finally, it returns to zero again.

We measure frequency in Hertz (Hz). Power grids in North America operate at 60 Hz. This means the current completes 60 full cycles every second. Most countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa use 50 Hz systems.

3.2.2 How Alternating Current in Generated?

Power stations use machines called alternators to generate alternating current. These machines spin wire coils through magnetic fields. As a coil rotates, it passes through the magnetic field lines at different angles. This rotation creates a voltage that rises and falls in a smooth wave pattern. The spinning motion directly converts into electrical oscillation.

The biggest benefit of AC is voltage transformation. Transformers can increase or decrease voltage with very little energy loss. A transformer has two wire coils wrapped around a shared iron core. When AC flows through the first coil, it creates a changing magnetic field. This magnetic field then induces AC in the second coil. The voltage ratio between input and output depends on how many turns each coil has.

3.2.3 How AC Powers Your Home

Power stations generate electricity at moderate voltages around 11,000 to 20,000 volts. Step-up transformers then boost this to 400,000 volts or even higher. This high voltage travels through long-distance transmission lines.

Why use such high voltage? Higher voltage means lower current for the same amount of power. Lower current means less energy gets wasted as heat in the wires. When power reaches your neighborhood, step-down transformers reduce the voltage. They bring it down to 230 volts or 120 volts for safe use in your home.

3.2.4 Limitations of Alternating Current

AC has its own limitation. You cannot store it directly in batteries. Batteries only accept direct current. To charge a battery from an AC outlet, you need a rectifier circuit. This circuit converts alternating current into direct current. Your phone charger contains such a circuit. It takes AC from the wall socket and produces DC that flows into your phone battery.

Today’s electrical systems combine both current types. AC dominates power generation and distribution. Its ability to transform voltage levels makes long-distance transmission efficient. DC dominates electronic devices and energy storage because of its stable one-way flow.

High-voltage DC transmission is also used for special applications. Very long transmission lines and underwater cables now use DC because AC losses become too high over such distances. The two forms of current work together in our modern electrical infrastructure.

4. Ohm’s Law: The Relationship Between Voltage, Current, and Resistance

Ohm’s Law is one of the most basic and useful relationships in electrical engineering. German physicist Georg Simon Ohm formulated this law in 1827. It describes the mathematical connection between three key circuit parameters. These are voltage, current, and resistance.

4.1 The Ohm’s Law Equation

Ohm’s Law states that current flowing through a conductor is directly proportional to the voltage across it. At the same time, it is inversely proportional to the resistance. The equation looks like this:

\(V=I\times R\)

Here V represents voltage in volts. I represents current in amperes. R represents resistance in ohms.

You can rearrange this equation to find any of the three values:

\(I=\frac{V}{R}\)

\(R=\frac{V}{I}\)

4.2 What These Relationships Tell Us

These equations reveal three important principles about how circuits behave.

First, when voltage increases and resistance stays the same, current increases by the same proportion. For example, if you double the voltage across a resistor, the current through it also doubles.

Second, when resistance increases and voltage stays the same, current decreases. Imagine a 12V battery connected to a 4Ω resistor. The current would be 3A. Now replace that resistor with an 8Ω resistor while keeping the same 12V battery. The current drops to 1.5A.

Third, to maintain a specific current through a higher resistance, you need a higher voltage. If you want 2A to flow through a 10Ω resistor, you need 20V. To push the same 2A through a 20Ω resistor, you need 40V.

4.3 Ohmic and Non-Ohmic Materials

Ohm’s Law applies strictly to ohmic materials. These are materials where resistance stays constant no matter how much voltage or current passes through them. Most metals show this ohmic behavior across a wide range of operating conditions. Copper, aluminum, and silver are good examples.

However, some materials and devices do not follow Ohm’s Law. We call these non-ohmic. Their resistance changes depending on voltage or current levels. Diodes allow current to flow easily in one direction but block it in the other. Transistors change their resistance based on control signals. Incandescent light bulb filaments increase their resistance as they heat up. None of these devices follow the simple linear relationship that Ohm’s Law describes.

5. Applications of Electric Current in Daily Life

Electric current powers almost every part of modern life. From tiny electronic gadgets to huge industrial operations, we depend on the flow of electrons for countless activities.

5.1 Lighting

Lighting was one of the first and most common uses of electric current. Different types of lights work in different ways. Incandescent bulbs heat a thin wire until it glows. Fluorescent tubes excite gas molecules to produce light. LED lights use semiconductor materials to emit light directly.

Each type has its own efficiency level. Incandescent bulbs waste most of their energy as heat. LEDs convert a much larger portion of electrical energy into light. This high efficiency has made LEDs the preferred choice for homes, offices, and street lighting. They also last much longer than older bulb types. This combination of efficiency and long life has helped reduce energy consumption around the world.

5.2 Heating and Cooling

Electric current runs our heating and cooling systems. Electric heaters use resistive heating elements to convert electrical energy directly into heat. When current flows through these high-resistance elements, they get hot. This is the same principle that makes a toaster heat your bread.

Air conditioners, refrigerators, and heat pumps work differently. They use electric motors to drive compressors. These compressors move heat from one place to another. Your refrigerator pumps heat from inside the cabinet to the outside. Your air conditioner pumps heat from inside your room to the outdoors.

Electric water heaters, space heaters, and industrial furnaces all use controlled current flow. Engineers can adjust the current to produce exactly the right amount of heat for each application.

5.3 Communication

Modern communication systems cannot function without electric current. Think about all the devices you use to communicate. Telephones, smartphones, computers, routers, and servers all need electricity. They use controlled current flow to encode information, transmit it, and decode it at the receiving end.

5.4 Transportation

Electric current plays a growing role in transportation. Electric trains and trams have used electric motors for more than a hundred years. These systems draw power from overhead wires or electrified rails.

Modern electric vehicles store energy in large battery packs. Electric motors convert this stored energy into motion. These vehicles produce zero emissions at the point of use. They also operate more efficiently than gasoline engines because electric motors waste less energy as heat.

Even traditional gasoline-powered cars depend on electric current. The starter motor uses battery power to crank the engine. The spark plugs need electrical current to ignite the fuel. Headlights, dashboard displays, power windows, and engine control computers all run on electricity from the car’s electrical system.

5.5 Medical Equipment

Hospitals and clinics use electric current in countless ways. Diagnostic machines help doctors see inside the human body. MRI machines use powerful electromagnets created by electric current. X-ray systems generate radiation using high-voltage electrical discharges. Electrocardiograph machines detect the tiny electrical signals produced by the heart itself.

Treatment devices also depend on electric current. Defibrillators deliver controlled electrical shocks to restart a stopped heart. Surgical lasers use electrical power to produce intense beams of light. Radiation therapy equipment requires precise electrical control to target cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue.

5.6 Industrial Manufacturing

Factories and manufacturing plants run entirely on electric current. Electric motors drive conveyor belts, pumps, fans, and countless other machines. Assembly lines move products from station to station using electrically powered systems.

Robotic arms weld car bodies together using electrical current to create the welding arc. Computer-controlled machine tools shape metal parts with extreme precision. Programmable controllers coordinate all these systems to work together.

Modern manufacturing simply could not exist without reliable electrical power. A single car factory might use as much electricity as a small town.

6. Example Questions on Electric Charge and Current

Q1: What is the current flowing through a circuit with a voltage of 12V and a resistance of 4Ω?

Answer: Using Ohm’s Law (\( I = \frac{V}{R} )\), we can calculate the current as:

\( I = \frac{12V}{4Ω} = 3A \)

Q2: How much charge passes through a point in a circuit in 10 seconds if the current is 2A?

Answer: Using the equation for current \(( I = \frac{Q}{t} )\), we can rearrange to solve for charge \( Q \):

\(Q = I \cdot t = 2A \cdot 10s = 20C \)

Q3: What is the force between two charges of \(3 \times 10^{-6} \, C\) and \(4 \times 10^{-6} \, C\) separated by a distance of 0.5m? (Use \( k = 8.99 \times 10^9 \, Nm^2/C^2 )\)

Answer: Using Coulomb’s Law \(( F = k \frac{q_1 q_2}{r^2} )\), we can calculate the force as:

\( F = 8.99 \times 10^9 \frac{(3 \times 10^{-6})(4 \times 10^{-6})}{(0.5)^2} = 0.4316 \, N \)

Q4: If a light bulb has a resistance of 240Ω and is connected to a 120V power source, what is the current flowing through the bulb?

Answer: Using Ohm’s Law \(( I = \frac{V}{R} )\), we can calculate the current as:

\( I = \frac{120V}{240Ω} = 0.5A\)

Q5: How long will it take for a charge of 30C to pass through a point in a circuit if the current is 5A?

Answer: Using the equation for current \(( I = \frac{Q}{t} )\), we can rearrange to solve for time \( t \):

\( t = \frac{Q}{I} = \frac{30C}{5A} = 6s \)

Q6: A circuit has a current of 3A and a resistance of 10Ω. What is the voltage across the circuit?

Answer: Using Ohm’s Law \(( V = I \cdot R )\), we can calculate the voltage as:

\( V = 3A \cdot 10Ω = 30V \)

Q7: What is the power consumed by an appliance that draws 2A of current from a 220V source?

Answer: Power \( P \) is given by the product of current \( I \) and voltage \( V \):

\( P = I \cdot V = 2A \cdot 220V = 440W \)

Q8: If the distance between two charges is tripled, by what factor does the force between them change?

Answer: According to Coulomb’s Law \(( F \propto \frac{1}{r^2} )\), if the distance \( r \) is tripled, the force \( F \) will be reduced by a factor of \( 3^2 \):

\( \text{New Force} = \frac{1}{3^2} = \frac{1}{9} \)

7. Frequently Asked Questions

Electric charge is a basic property of matter, carried by particles like electrons and protons, that causes them to experience a force in an electromagnetic field. Electric current is the rate of flow of this charge through a conductor. In simple terms, charge is the “stuff,” and current is the “stuff in motion.”

This is a fundamental rule of electrostatics. Particles with the same type of charge (both positive or both negative) exert a repulsive force on each other, pushing them apart. Conversely, particles with opposite charges (one positive and one negative) exert an attractive force, pulling them together.

The smallest unit of charge is called the elementary charge (e), which is the magnitude of charge on a single proton or electron.

Conventional current is defined as the direction that positive charges would flow, which is from the positive terminal to the negative terminal of a power source. However, in most metal conductors, it is the negatively charged electrons that actually move, flowing from the negative terminal to the positive terminal. For historical reasons and consistency, electrical engineers almost always use the conventional current direction in circuit analysis.

The actual net forward movement of electrons in a wire, known as drift velocity, is surprisingly slow—often less than a millimeter per second. However, the electrical signal itself travels at nearly the speed of light because the electric field that pushes the electrons propagates through the wire almost instantaneously.

No, electric charge is conserved. The law of conservation of charge states that charge can neither be created nor destroyed, only moved from one place to another. In a circuit, a power source does work to move charges, but the total amount of charge remains constant.