Electrical protection devices play a major role in keeping our homes, offices, and industrial facilities safe from electrical hazards. When it comes to protecting electrical circuits from overloads and short circuits, two devices have been used for decades: circuit breakers and fuses.

Both of these devices serve the same primary purpose to interrupt the flow of electricity when something goes wrong in the circuit. However, they work differently and have their own sets of advantages and disadvantages.

In this technical guide we will discuss everything you need to know about circuit breakers and fuses, their working principles, applications, and which one might be the better choice for different situations.

1. What is a Fuse?

A fuse is one of the oldest and simplest electrical protection devices. It consists of a metal wire or strip that melts when too much current flows through it. Once the fuse melts, the circuit is broken, and the flow of electricity stops immediately.

The metal element inside a fuse is specifically designed to have a lower melting point than the wires in the circuit it protects. This means the fuse will always melt before the circuit wires get damaged by excessive current.

Fuses come in various shapes and sizes depending on their application. You can find small glass tube fuses in electronics, plug fuses in older residential buildings, and large high-voltage fuses in industrial power systems.

The main characteristic of a fuse is its current rating. This rating tells you the maximum current the fuse can carry without melting. For example, a 15-amp fuse will blow if the current exceeds 15 amperes for a certain period.

1.1 How Does a Fuse Work?

The working principle of a fuse is based on the heating effect of electric current. When electricity flows through a conductor, it generates heat. The amount of heat produced depends on the resistance of the conductor and the amount of current flowing through it.

Under normal operating conditions, the fuse element carries the rated current without generating enough heat to melt. The heat produced is dissipated into the surrounding air, and the fuse remains intact.

However, when an overload or short circuit occurs, the current flowing through the fuse increases beyond its rated capacity. This causes the fuse element to heat up rapidly. Within milliseconds to a few seconds (depending on the severity of the fault), the metal element reaches its melting point and breaks apart.

Once the fuse element melts, the circuit is opened, and no more current can flow. This action is irreversible and the fuse cannot be reset and must be replaced with a new one.

1.2 Types of Fuses

Fuses are available in many different types, each designed for specific applications. Here are the most common ones:

1.2.1 Cartridge Fuses

These are cylindrical fuses with metal end caps. They are commonly used in industrial applications and older residential electrical panels. Cartridge fuses can handle higher currents and are available in various sizes from small to very large.

1.2.2 Plug Fuses

Also known as screw-in fuses, these were common in older homes built before the 1960s. They have a threaded base that screws into a socket, similar to a light bulb. Plug fuses are still used in some applications today.

1.2.3 Blade Fuses

These are the flat, plastic-bodied fuses you find in automobiles. They come in mini, standard, and maxi sizes and are color-coded based on their current rating.

1.2.4 High Rupturing Capacity (HRC) Fuses

These fuses are designed for high-current applications where the fault current can be extremely high. They contain a special filling material (usually quartz sand) that helps extinguish the arc when the fuse blows.

1.2.5 Semiconductor Fuses

These are ultra-fast fuses designed to protect sensitive semiconductor devices like diodes, thyristors, and transistors. They can interrupt the circuit within microseconds.

1.2.6 Rewireable Fuses

Also called kit-kat fuses, these allow the user to replace just the fuse wire instead of the entire fuse unit. They are common in some regions but are gradually being phased out due to safety concerns.

2. What is a Circuit Breaker?

A circuit breaker is an automatic electrical switch designed to protect an electrical circuit from damage caused by overload or short circuit. Unlike a fuse, a circuit breaker can be reset after it trips making it reusable.

When a fault occurs, the circuit breaker automatically interrupts the current flow. After the fault is corrected, you can simply flip the switch back to the “ON” position, and the circuit is restored. This makes circuit breakers more convenient and economical in the long run.

Circuit breakers come in various sizes and types, from small breakers used in residential panels to massive breakers used in power transmission systems that can handle thousands of amperes.

Modern homes and commercial buildings almost exclusively use circuit breakers instead of fuses. They offer better protection, easier operation, and can be equipped with additional safety features like ground fault protection.

2.1 How Does a Circuit Breaker Work?

Circuit breakers use two main mechanisms to detect and interrupt fault currents: thermal and magnetic.

2.1.1 Thermal Mechanism

This mechanism uses a bimetallic strip made of two different metals bonded together. When excess current flows through the breaker, the strip heats up. Because the two metals expand at different rates, the strip bends. When it bends enough, it releases a latch that trips the breaker and opens the circuit.

The thermal mechanism is designed to respond to overload conditions. It takes some time for the strip to heat up and bend, so small, brief overloads may not trip the breaker. This prevents nuisance tripping during normal operations like motor startup.

2.1.2 Magnetic Mechanism

This mechanism uses an electromagnet to detect short circuits. When a large fault current flows through the breaker, it creates a strong magnetic field in the electromagnet. This magnetic force is strong enough to pull a metal armature that releases the tripping mechanism instantly.

The magnetic mechanism provides fast response to short circuits, which can have very high currents that need to be interrupted immediately to prevent damage and fire.

Most modern circuit breakers combine both mechanisms and are called thermal-magnetic circuit breakers. They provide protection against both overloads and short circuits.

2.2 Types of Circuit Breakers

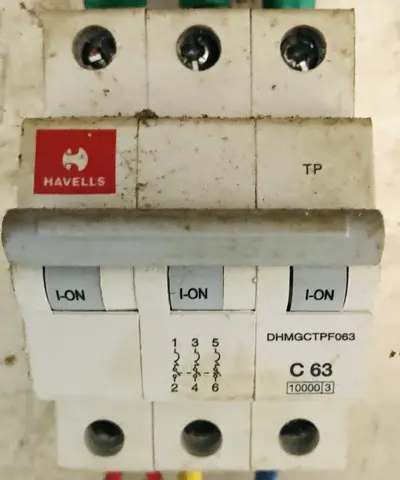

2.2.1 Miniature Circuit Breakers (MCB)

Miniature Circuit Breakers are the most common type found in residential and commercial electrical panels. They are designed for currents up to 100 amperes and are available in single-pole, double-pole, and triple-pole configurations.

2.2.2 Molded Case Circuit Breakers (MCCB)

MCCBs are used for higher current applications, ranging from 100 to 2500 amperes. They are commonly found in industrial settings and can be equipped with adjustable trip settings.

2.2.3 Air Circuit Breakers (ACB)

Air Circuit Breakers are large circuit breakers used in low-voltage power distribution systems. They use air as the arc extinguishing medium and can handle currents up to 6300 amperes.

2.2.4 Vacuum Circuit Breakers (VCB)

VCBs use a vacuum as the arc quenching medium. They are commonly used in medium-voltage applications (up to 38 kV) and offer excellent performance with minimal maintenance.

2.2.5 Oil Circuit Breakers (OCB)

Oil Circuit Breakers use oil as both the arc extinguishing medium and insulating medium. They were common in older power systems but are now being replaced by vacuum and SF6 breakers.

2.2.6 SF6 Circuit Breakers

SF6 Circuit Breakers use sulfur hexafluoride gas as the arc quenching medium. SF6 is an excellent insulator and arc extinguisher, making these breakers ideal for high-voltage applications.

2.2.7 GFCI Breakers

Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter breakers provide additional protection against electric shock. They monitor the current balance between the hot and neutral wires and trip if they detect a ground fault.

2.2.8 AFCI Breakers

Arc Fault Circuit Interrupter breakers detect dangerous electrical arcs that can cause fires. They are now required in bedrooms and other areas in many building codes.

3. Differences Between Circuit Breaker and Fuse

Let’s examine the main differences between these two protection devices:

- Working Principle: Fuses work by melting a metal element when overcurrent flows through them. Circuit breakers work using thermal and/or magnetic mechanisms to trip a switch mechanism.

- Reusability: Fuses are single-use devices. Once they blow, they must be replaced. Circuit breakers can be reset and reused multiple times without replacement.

- Response Time: Fuses generally have faster response times, especially during short circuits. They can interrupt the circuit within a few milliseconds. Circuit breakers, while fast, usually take slightly longer to trip.

- Cost: Individual fuses are less expensive than circuit breakers. However, since fuses need to be replaced every time they blow, the long-term cost may be higher.

- Breaking Capacity: High-quality fuses can have higher breaking capacities than circuit breakers of similar ratings. This makes fuses preferred in some high-current industrial applications.

- Protection Level: Circuit breakers can be equipped with various additional protections like ground fault and arc fault detection. Fuses only provide overcurrent protection.

- Maintenance: Fuses require no maintenance but need replacement after every operation. Circuit breakers may require periodic testing and maintenance but can last for many years.

3.1 Comparison Table: Circuit Breaker Vs Fuse

| Feature | Fuse | Circuit Breaker |

|---|---|---|

| Operation | Automatic (one-time) | Automatic with manual reset |

| Reusability | No | Yes |

| Response Time | Faster | Slightly slower |

| Initial Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Long-term Cost | Higher (replacements) | Lower |

| Breaking Capacity | Can be very high | Limited by design |

| Indication | May not be clear | Clear position indicator |

| Additional Protection | Overcurrent only | Can include GFCI, AFCI |

| Maintenance | None (replacement only) | Periodic testing needed |

| Installation | Simple | More complex |

| Sensitivity Adjustment | Fixed | Can be adjustable |

4. Advantages and Disadvantages of Fuses

4.1 Advantages of Fuses

Fuses have several benefits that make them the preferred choice in certain applications:

- Simple Design: Fuses have no moving parts, making them extremely reliable. There is nothing to wear out or fail mechanically.

- Fast Operation: High-quality fuses can interrupt fault currents faster than circuit breakers. This is particularly important when protecting sensitive equipment.

- High Breaking Capacity: Fuses can be designed to safely interrupt very high fault currents without exploding or releasing dangerous gases.

- Low Cost: For one-time installations or applications where faults are rare, fuses are more economical than circuit breakers.

- No Maintenance: Fuses do not require any maintenance. You simply replace them when they blow.

- Current Limiting: Some fuses can limit the let-through current during a fault, reducing the stress on downstream equipment.

4.2 Disadvantages of Fuses

Despite their benefits, fuses have some drawbacks:

- Single Use: The most obvious disadvantage is that fuses cannot be reset. You need to keep spare fuses on hand and replace them after every fault.

- Replacement Time: Replacing a fuse takes time, which can be a problem in industrial settings where downtime is costly.

- Wrong Replacement Risk: There is always a risk that someone might install a fuse with the wrong rating, either too low (causing nuisance blowing) or too high (providing inadequate protection).

- Degradation: Fuse elements can degrade over time due to repeated heating and cooling cycles, even without blowing. This can lead to unexpected fuse failures.

- No Remote Indication: Standard fuses do not provide remote indication of their status, making them less suitable for automated systems.

5. Advantages and Disadvantages of Circuit Breakers

5.1 Advantages of Circuit Breakers

Circuit breakers offer numerous benefits for modern electrical systems:

- Reusability: The ability to reset a circuit breaker after it trips saves money and reduces downtime. You don’t need to keep spare parts on hand.

- Easy Operation: Resetting a circuit breaker is as simple as flipping a switch. No tools or special skills are required.

- Clear Indication: Circuit breakers clearly show their status (on, off, or tripped) through their handle position.

- Multiple Protection Types: Modern circuit breakers can include ground fault, arc fault, and other advanced protection features.

- Adjustable Settings: Some circuit breakers allow you to adjust the trip current and time settings to match the specific needs of the circuit.

- Remote Operation: Circuit breakers can be equipped with motor operators for remote switching, which is useful in automated systems.

5.2 Disadvantages of Circuit Breakers

Circuit breakers also have some limitations:

- Higher Initial Cost: Circuit breakers cost more than fuses, especially for high-current ratings or advanced protection features.

- Slower Response: For very fast fault current interruption, fuses may perform better than circuit breakers.

- Maintenance Requirements: Circuit breakers have moving parts that can wear out or fail. They need periodic testing and maintenance to remain reliable.

- Limited Breaking Capacity: For very high fault currents, fuses may be the only practical option because they can handle higher breaking capacities.

- Complexity: The internal mechanisms of circuit breakers are more complex, which can lead to failure modes that don’t exist in fuses.

6. When to Use a Fuse

Fuses are the better choice in the following situations:

High Fault Current Applications: In industrial power systems where fault currents can be extremely high, fuses with high breaking capacities are often the only option.

Protecting Semiconductors: Fast-acting semiconductor fuses can protect thyristors, diodes, and transistors better than circuit breakers.

Cost-Sensitive Applications: When the initial cost is a major concern and faults are expected to be rare, fuses make economic sense.

Space-Limited Installations: Fuses can be more compact than circuit breakers of equivalent ratings.

Backup Protection: Fuses are sometimes used as backup protection behind circuit breakers in case the breaker fails to trip.

Automotive Applications: Blade fuses are the standard for automotive electrical systems due to their compact size and low cost.

7. When to Use a Circuit Breaker

Circuit breakers are preferred in these situations:

Residential and Commercial Buildings: Modern building codes in most countries require circuit breakers for new construction.

Frequent Fault Conditions: If faults occur regularly (such as in a training lab), circuit breakers save the cost and inconvenience of frequent fuse replacement.

Remote or Automated Systems: When remote operation or automatic reclosing is needed, circuit breakers are the only practical choice.

Ground Fault Protection: GFCI breakers provide protection against electric shock that fuses cannot offer.

Arc Fault Protection: AFCI breakers detect dangerous arcing conditions that could cause fires.

General Convenience: For most applications, the convenience of resettable protection outweighs the slightly higher cost of circuit breakers.

8. Conclusion

Both circuit breakers and fuses serve the important purpose of protecting electrical circuits from damage due to overcurrent conditions. Each has its own set of advantages and is better suited for specific applications.

Fuses offer simplicity, fast response, and high breaking capacities at a low initial cost. They are ideal for industrial applications, semiconductor protection, and situations where faults are rare.

Circuit breakers provide convenience through reusability, clear indication, and the ability to incorporate advanced protection features. They are the standard choice for residential and commercial buildings and situations where frequent operation is expected.

9. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Yes, in many cases you can upgrade from a fuse panel to a circuit breaker panel.

A circuit breaker trips due to overload, short circuit, or ground fault. First, check if you have too many devices on the circuit. If that’s not the issue, there may be a short circuit in the wiring or a faulty appliance. If the problem persists, consult an electrician.

Installing a higher-rated fuse is dangerous and should never be done. The fuse is designed to protect the wiring, and a higher-rated fuse will allow more current than the wire can safely handle. This can cause the wiring to overheat and start a fire.

Neither is inherently safer than the other when properly used. Fuses can react faster to short circuits, while circuit breakers offer additional protection options like GFCI and AFCI. The safety depends on proper selection, installation, and use.

Fuses are still used because they offer advantages in certain applications. They can interrupt higher fault currents, respond faster, and are more economical for one-time protection. In industrial settings and for semiconductor protection, fuses remain the preferred choice.

Yes, in many systems, fuses and circuit breakers are used together at different levels. For example, a main circuit breaker might protect a panel that has fused disconnects for individual motor circuits. This provides layered protection and allows each device to be optimized for its specific role.