Electrical earthing is the backbone of any safe electrical system. Whether it is a small residential building or a massive 400kV substation, the safety of human life and equipment depends entirely on how well the earthing system works. But simply burying a copper plate or driving a rod into the ground is not enough. We must verify if that connection to the earth is actually good enough to carry fault currents away.

This verification is done through the Earth Pit Resistance Measurement Test.

In this technical guide, we will explore what Earth Pit Resistance Measurement Test is, how to perform it using the standard “Three Point Method,” and understand the physics behind it using simple real-life examples.

What is Earth Pit Resistance?

Earth pit resistance refers to the electrical resistance measured between the earth electrode and the surrounding soil. This parameter is improtant because it directly affects how effectively a grounding system can dissipate fault currents. When a fault occurs in an electrical installation, the current must flow through the earth electrode into the soil with minimal resistance to prevent dangerous voltage rises that could cause electric shock or equipment damage. Regular earth pit resistance testing is therefore a mandatory requirement in electrical installations, as specified by international standards including IEEE 81, IEC 60364, and IS 3043.

To visualize earth resistance, imagine your electrical system is a house with a plumbing system, and the fault current is unwanted waste water. The earth pit acts like the main drain pipe that leads this water out of your house and into the municipal sewer (the earth).

If this drain pipe is wide and clean (low resistance), any sudden rush of water (fault current) flushes away instantly, keeping your house dry and safe. However, if the drain pipe is clogged with dirt or is too narrow (high resistance), the water cannot escape fast enough. It backs up, leaks, and causes damage to the floors and walls.

Similarly, if your earth pit resistance is high, the dangerous electrical current from a fault cannot escape into the ground quickly. Instead, it “backs up” into the metal bodies of your equipment (like transformer tanks or motor casings). If a person touches this equipment, the current flows through them instead of the ground, leading to a fatal electric shock.

How the Earth Tester Works

An earth tester is a specialized instrument designed to safely measure the resistance between an earth electrode and the surrounding soil using non-destructive testing methods.

The hand-operated earth tester, the most commonly used type in field applications, employs a hand-crank driven direct current (DC) generator as its power source. The operator rotates the generator handle, which drives the electrical components inside. The tester incorporates two key components: a current reverser and a rectifier both mounted on the generator shaft. These components synchronize their operation to convert the DC output into alternating current (AC) for injection into the earth, then convert the received AC signal back to DC for instrument display.

Why AC current is used instead of DC

While the generator produces DC, earth testers use AC current for the actual soil injection through the current reverser. The reason is that a prolonged DC current would cause electrolytic effects similar to water electrolysis. The DC would gradually cause bubbles of hydrogen and oxygen to form around the electrodes, creating a gaseous barrier that blocks current flow and produces unreliable measurements. Using AC current eliminates this electrolytic effect, ensuring accurate and repeatable results. The frequency of the AC used is selected to avoid commercial power frequencies (50 Hz or 60 Hz) to reduce interference from nearby electrical installations. Typical earth testers use frequencies like 16 Hz or 400 Hz.

Inside the tester, there is one current coil and one pressure (potential) coil. The current coil measures the actual current flowing through the soil between the test electrodes. The potential coil measures the voltage drop between the earth electrode under test and the potential measuring electrode.

The earth tester’s pointer movement is proportional to the ratio of voltage to current following Ohm’s Law (R = V/I) displaying the resistance directly on a calibrated scale.

Measurement of Earth Resistance (Three Point Method)

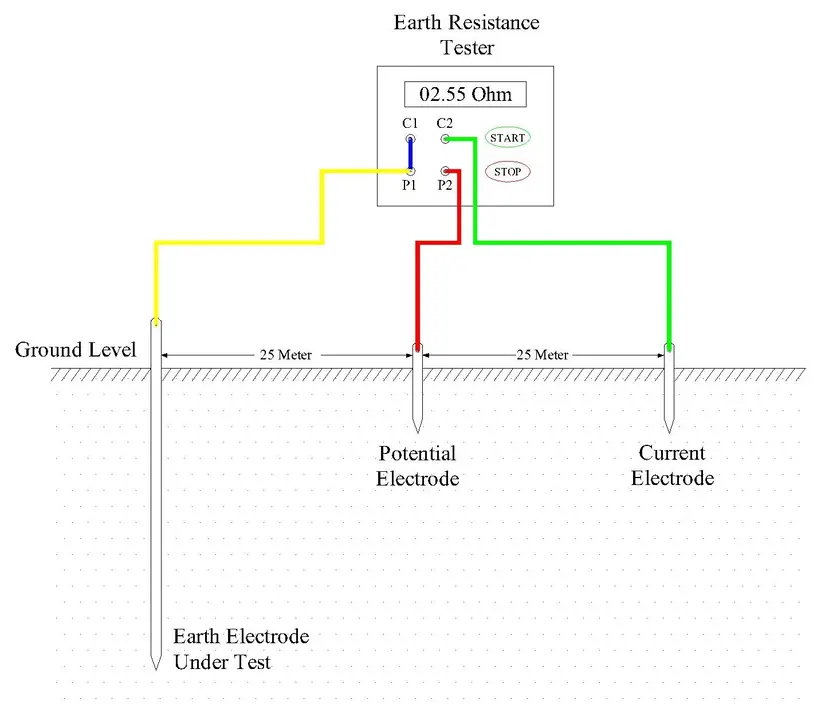

The most reliable and common way to measure earth resistance is the Three Point Method (also known as the Fall of Potential Method). As shown in the images below, this method involves your main earth electrode and two auxiliary spikes.

Step 1: Isolation

Before starting, you must disconnect the pit earthing connection from the main grid or the equipment it is protecting. If you measure it while connected, your reading will include the parallel resistance of the entire grid, giving you a falsely low value. The earth electrode under test must be isolated.

Step 2: Connections and Spike Placement

The Earth Tester has four terminals: C1, P1, P2, and C2. For this test, short the C1 and P1 terminals together and connect them to the earth electrode (pipe) you are testing.

Next, you need to drive two auxiliary spikes into the ground. These are small metal rods that complete the circuit. Connect the P2 terminal to the first spike (Potential Spike) and the C2 terminal to the second spike (Current Spike).

Step 3: Distance and Alignment

The placement of these spikes is critical. They must be driven into the earth in a straight line relative to the test electrode.

- The first spike (connected to P2) should be placed 25 meters away from the test electrode.

- The second spike (connected to C2) should be placed 25 meters further away from the first spike.

This makes the total distance from the test electrode to the last spike 50 meters. We maintain this specific distance to ensure there is no “mutual interference” between the electrical fields of the individual spikes. If they are too close, the “zones of influence” overlap, and the resistance reading will be inaccurate.

Step 4: Taking the Reading

Once connected, rotate the handle of the Earth Tester generator at a specific speed (usually around 160 RPM for older analog models, or simply press the ‘Test’ button on digital ones). The instrument injects current between C1 and C2 and measures the potential drop between P1 and P2. The scale will directly indicate the earth resistance in Ohms (Ω).

Acceptable Limits for Earth Resistance

After you get the value, you need to know if it is good or bad. The acceptable limit depends on the type of installation, but general safety standards (like IS 3043) provide clear benchmarks.

| Installation Type | Acceptable Resistance Value |

|---|---|

| Large Power Stations (with Grid) | ≤ 0.5 Ω to 1.0 Ω |

| Major Substations | ≤ 1.0 Ω |

| Small Substation / Industrial Plant | ≤ 2.0 Ω |

| Domestic / Ordinary Earth Pit | ≤ 5.0 Ω (standard) / ≤ 10 Ω (acceptable without grid) |

| Tower Footing | ≤ 10 Ω |

A value of less than or equal to 1Ω is ideal for systems connected to a grid. For isolated pits without a grid, a value up to 10Ω is often considered the upper limit of acceptability, though lower is always safer.

Test Report Format

Alternative Testing Methods for Earth Pit Resistance

While the three-point fall-of-potential method remains the gold standard, several alternative methods are used depending on site conditions, grounding system configuration, and practical constraints.

Selective Testing Method

The selective testing method is employed when testing individual earth electrodes within interconnected grounding systems where complete disconnection is not practical or possible.

This method uses a current clamp (also called a clamp meter) that is placed around the conductor under test without the need to disconnect it from the system. The clamp meter uses an AC signal to inject a known test current into the electrode being measured. The method requires two conventional auxiliary electrodes (stakes) positioned 20 meters away from the electrode under test, one for potential reference and one at remote distance.

Wenner Four-Point Method

The Wenner four-point method, also called the Wenner method or four-electrode method, is primarily used for measuring soil resistivity rather than individual earth electrode resistance. However, it is often used during the design phase of grounding systems to characterize the soil at a site.

Four small electrodes of equal size are driven into the soil at the same depth in a straight line, with equal spacing between them. Current is injected between the outer two electrodes, and voltage is measured between the inner two electrodes. This configuration is advantageous because the potential electrodes measure voltage in the region of most uniform electric field, providing good repeatability.

The Wenner method requires taking measurements at multiple electrode spacings—typically ranging from 0.5 meters to 10 meters or more. Each measurement represents the average soil resistivity at a depth approximately equal to the electrode spacing. By repeating measurements at increasing distances, the engineer obtains a profile of soil resistivity versus depth.

This information is important for designing the optimal earth pit depth and diameter.

The Wenner method is more labor-intensive than the fall-of-potential method because it requires driving multiple sets of electrodes, but it provides valuable characterization of site conditions.

Clamp-On Method (Stakeless Testing)

The clamp-on method, also called stakeless testing, is a convenience method that eliminates the need to drive auxiliary electrodes into the ground. This is a significant advantage in urban areas, hard soil, or locations where ground disturbance is not permitted.

The operator uses a specialized clamp-on earth resistance meter that clamps around the grounding conductor without breaking the circuit. The clamp meter injects an AC test signal through the conductor and measures the current flowing in the grounding loop. The resistance is calculated using Ohm’s Law.

The limitation of clamp-on testing is that it measures the resistance of the entire parallel path through which current can return to the grounding system, not just the individual electrode under test. In installations with multiple grounding paths such as water pipes, structural steel, or multiple electrodes, the clamp meter measures the combined resistance of all parallel paths in series.

This can result in readings that are lower than the actual earth pit resistance because multiple paths share the current. Therefore, clamp-on method results should be viewed as quick screening measurements rather than precise earth pit resistance values, particularly in complex multi-electrode systems. The method is most accurate for simple installations with limited parallel return paths.

Why Do Earth Resistance Values Vary?

You might measure an earth pit today and get 2.5Ω, and measure it again in summer and get 8.0Ω. This happens because earth resistance is heavily dependent on the resistivity of the soil.

Moisture content is the biggest factor. Dry soil acts like an insulator. When the soil is moist, the salts dissolve in the water, creating a conductive electrolyte that helps current flow easily. This is why we often water the earth pits before testing or during dry seasons.

Temperature also plays a role. Frozen ground has extremely high resistance, while warm soil conducts better. The physical composition of the soil matters too; rocky or sandy soil drains water effectively but has poor electrical conductivity, whereas clay or loamy soil retains moisture and offers much better (lower) resistance.

By performing this test regularly—ideally during the dry season when resistance is naturally highest—you ensure that your electrical protection system will not fail when it matters most.

Standards and Regulations Governing Earth Pit Testing

Several international and national standards specify procedures and requirements for earth pit resistance measurement.

- IEEE Standard 81-2012 (now updated to IEEE 81-2025) is the guide for measuring earth resistivity, ground impedance, and earth surface potentials of grounding systems. The standard covers multiple testing methods including the fall-of-potential method, two-point method, four-point method, clamp-on method, and slope method. IEEE 81 emphasizes safety considerations, sources of measurement error, and practical guidance for obtaining reliable results. The standard notes that extreme precision is rarely possible due to soil variability, and measurements should be made carefully using the most suitable available method with thorough understanding of potential error sources.

- IEC 60364-5-54 and IEC 60364-6 cover earthing requirements for low-voltage electrical installations. These standards specify that earth electrodes must be suitable for the soil conditions and must achieve the resistance value required for protective device coordination. The standards require periodic testing of earth systems to verify continued compliance with design specifications.

- IS 3043:2018 is the Indian Standard Code of Practice for Earthing. Clause 27 of IS 3043 establishes earth resistance requirements. The standard specifies that the continuity resistance of the earth return path through the earth grid should be maintained as low as possible and in no case greater than 1 ohm for main earthing conductors. IS 3043 also requires that earth electrode resistance should be within “reasonable limits” and considers the coordination between practically obtainable earth resistance values and protective device settings.

- BS 7430:1998 is the British Standard Code of Practice for Earthing. This standard provides comprehensive guidance on earthing design and testing requirements for the United Kingdom and commonwealth countries.

- RDSO (Railway Board) standards specify earth resistance requirements for Indian railway infrastructure. These standards typically require earth resistance at MEEB (Main Earthing Equipment Busbar) locations not exceeding 1 ohm, with provisions for parallel earth pits when single electrodes cannot achieve this value in high-resistivity soils.

Conclusion

Earth pit resistance measurement is an important procedure that ensures electrical safety and system reliability in all electrical installations. The three-point fall-of-potential method provides accurate, reliable measurements when properly executed according to IEEE and international standards.