Dissolved Gas Analysis (DGA) is one of the most critical diagnostic techniques used to assess the internal health of oil-filled transformers. This non-invasive test analyzes the concentration and composition of gases dissolved in transformer oil, providing early warning signs of developing faults such as overheating, partial discharge, and arcing. By detecting these incipient faults before they lead to catastrophic failures, DGA helps utilities and industrial facilities prevent costly equipment damage and unplanned outages.

The importance of DGA cannot be overstated in transformer maintenance programs. While physical and chemical oil tests reveal the condition of the insulating fluid itself, only DGA can provide insight into the internal condition of the transformer’s active parts—the windings, core, and insulation system—without requiring the unit to be taken out of service. This makes it an indispensable tool for predictive maintenance strategies.

Dissolved Gas Analysis Test

Transformer oil serves multiple critical functions: electrical insulation, heat dissipation, and arc extinction. During normal operation and fault conditions, the oil and cellulosic insulation materials decompose due to electrical and thermal stresses, producing various hydrocarbon gases and oxides of carbon. These gases dissolve in the oil and can be extracted and analyzed to diagnose the transformer’s condition.

The principle behind DGA is straightforward yet powerful. Different fault conditions produce characteristic patterns of gas generation. For example, high-temperature thermal faults predominantly produce ethylene and methane, while electrical arcing generates large quantities of hydrogen and acetylene. By identifying which gases are present and in what concentrations, skilled analysts can determine not only whether a fault exists but also its probable nature and severity.

Key Gases and Their Significance

The principal gases analyzed during DGA include hydrogen \((H_2)\), methane \((CH_4)\), ethane \((C_2H_6)\), ethylene \((C_2H_4)\), acetylene \((C_2H_2)\), carbon monoxide \((CO)\), carbon dioxide \((CO_2)\), oxygen \((O_2)\), and nitrogen \((N_2)\). Each gas provides specific diagnostic information:

- Hydrogen \((H_2)\) is primarily produced by partial discharge (corona) and is often the first indicator of electrical stress in the insulation system. Elevated hydrogen levels can signal corona discharge occurring in oil-filled voids or at sharp edges of conductors.

- Methane \((CH_4)\) and ethane \((C_2H_6)\) are typically generated during low-temperature thermal decomposition of oil, usually below 300°C. Their presence often indicates localized overheating or poor circulation causing hot spots.

- Ethylene \((C_2H_4)\) becomes the dominant hydrocarbon gas when oil temperatures exceed 300°C, indicating more severe thermal faults. High concentrations suggest significant overheating that may be damaging both oil and solid insulation.

- Acetylene \((C_2H_2)\) is the signature gas for high-energy electrical faults such as arcing. Because acetylene is only produced at temperatures exceeding 700°C, its presence—even in small quantities—demands immediate attention, as it indicates potentially catastrophic conditions.

- Carbon monoxide \((CO)\) and carbon dioxide \((CO_2)\) result from thermal decomposition of cellulosic insulation materials like paper and pressboard. The ratio of \((CO_2)\) to \((CO)\) helps assess the severity of cellulose degradation, with higher \((CO)\) levels indicating more serious overheating of solid insulation.

DGA Test Procedures

Performing an accurate dissolved gas analysis requires careful attention to sampling techniques, gas extraction methods, and analytical procedures. The entire process must be conducted according to established standards to ensure reliable results.

Sample Collection Procedure

The quality of DGA results depends critically on proper oil sampling techniques. Contaminated or improperly handled samples can lead to erroneous conclusions and potentially dangerous operating decisions.

Step 1: Relieve Oil Tank Pressure

Begin by carefully relieving the pressure inside the transformer’s oil conservator or main tank. Oil-filled transformers are typically operated under a slight positive pressure to prevent moisture ingress and maintain oil circulation. Use the pressure relief valve to slowly depressurize the system to atmospheric pressure. This step prevents oil from spraying when the sampling valve is opened.

Step 2: Purge the Sampling Valve and Hose

Locate the oil sampling valve, typically positioned at the lower portion of the transformer tank or on dedicated sampling ports. Remove the protective cap and open the drain valve to purge any moisture, dirt, sediment, or oxidized oil that may have accumulated in the valve body or attached hose. Allow oil to flow into a waste container for 10-15 seconds. This purging step is essential because contaminants trapped in the sampling port can significantly affect test results.

Step 3: Draw the Oil Sample

Prepare the sampling syringe or container according to the laboratory’s specifications. Most DGA analysis requires specialized gas-tight syringes, typically with 50-100 ml capacity. Connect the clean syringe to the purged sampling valve using appropriate adapters. Open the valve and slowly draw the oil sample by pulling the syringe plunger.

For the most accurate results, the sample should be taken from the middle zone of the oil tank rather than from the very top or bottom, as this provides a representative sample of the bulk oil condition.

Step 4: Remove Air and Prepare for Transport

With the syringe valve closed to the sampling port and pointed upward, carefully push the plunger to expel all air bubbles and a small amount of oil until exactly the required sample volume remains (typically 50 ml). Immediately set the syringe valve to the closed position to seal the sample. Wipe the exterior of the syringe clean of oil residue to prevent contamination during handling.

Pack the sealed syringe in a protective container, keeping it away from heat sources and direct sunlight. Temperature fluctuations can affect gas solubility and lead to measurement errors. Label the sample clearly with the transformer identification, sampling date and time, oil temperature, and any relevant operational information.

Important Sampling Considerations

Temperature Management: The transformer should ideally be at a stable, moderate temperature when sampling. Avoid taking samples immediately after heavy loading or when the transformer is very hot, as elevated temperatures affect gas solubility and can produce misleading results. If sampling must be done on a hot transformer, record the oil temperature accurately for the laboratory.

Sample Mixing: Once collected and sealed, gently invert the syringe several times to ensure the oil is well-mixed and gases are evenly distributed throughout the sample. However, avoid vigorous shaking that could cause gas to come out of solution.

Chain of Custody: Maintain proper documentation throughout the sampling and transport process. Record all relevant information including transformer nameplate data, recent loading history, any unusual events or alarms, and the exact sampling location.

Transport to Laboratory: Ship samples to a certified DGA laboratory as soon as possible after collection. Most standards recommend analysis within 2-4 weeks of sampling, though sooner is always better. Use a shipping method that avoids extreme temperatures and rough handling.

Gas Extraction Methods

Once the oil sample reaches the laboratory, the dissolved gases must be extracted from the oil and prepared for analysis. Several standardized extraction methods exist, each with different capabilities and accuracy levels.

Vacuum Extraction Method (ASTM D3612)

The vacuum extraction method is considered the most complete and accurate technique for DGA. In this approach, the oil sample is subjected to a very low absolute pressure (high vacuum) at a controlled temperature, typically between 30-60°C. Under these conditions, the dissolved gases are released from the oil and collected in a gas chamber.

Modern vacuum extraction systems use multi-stage extraction, where the same oil sample is repeatedly exposed to vacuum conditions until no additional gas is released. This multi-stage approach achieves extraction efficiencies exceeding 98%, compared to only 45% for single-stage vacuum extraction. The extracted gases are then compressed using mercury displacement or mechanical pumps, measured precisely, and transferred to the gas chromatograph for analysis.

Advanced extraction systems employ an innovative method where the oil column itself acts as a vacuum pump piston, creating vacuum by pumping oil out of the extraction chamber and then spraying the oil back through the vacuum to extract gases. This eliminates mechanical vacuum pumps and reduces maintenance requirements.

Headspace Sampling Method (ASTM D3612 Method C)

Headspace sampling is a simpler, faster alternative to vacuum extraction. A measured volume of oil (typically 10 ml) is placed in a sealed vial with a controlled headspace volume filled with an inert gas such as argon or nitrogen. The vial is agitated at a constant temperature for a specified time (usually 5-10 minutes) to establish equilibrium between gases dissolved in the oil and gases in the headspace.

An aliquot of the headspace gas is then injected directly into the gas chromatograph. The concentration of dissolved gases in the oil is calculated from the headspace concentrations using Henry’s Law constants, which describe the equilibrium distribution of gases between liquid and gas phases. While headspace sampling is convenient and widely used, its accuracy depends heavily on precise control of oil volume, headspace volume, temperature, and equilibration time.

Stripping Method

In the stripping or carrier gas method, an inert gas (typically nitrogen or helium) is bubbled through the oil sample at a controlled flow rate and temperature. The carrier gas strips the dissolved gases from the oil, and the gas stream is collected and analyzed. This method is less commonly used than vacuum extraction or headspace sampling due to lower efficiency and greater complexity.

Gas Chromatography Analysis

After extraction, the gas mixture is analyzed using gas chromatography (GC), the gold standard analytical technique for identifying and quantifying individual gas components. The gas chromatograph separates the gas mixture into individual components based on their physical and chemical properties as they pass through a chromatographic column packed with specific stationary phase materials.

Different gases travel through the column at different rates depending on their molecular weight, polarity, and interaction with the stationary phase. As each gas emerges from the column at its characteristic retention time, it passes through one or more detectors.

Flame Ionization Detector (FID) is used to detect and quantify hydrocarbon gases \((CH_4, C_2H_6, C_2H_4, C_2H_2)\). The FID burns the hydrocarbon gases in a hydrogen-air flame, producing ions that create a measurable electrical current proportional to the gas concentration.

Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) measures hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. The TCD compares the thermal conductivity of the carrier gas stream with and without sample gases, producing a signal proportional to gas concentration.

Modern transformer oil gas analyzers (TOGA) systems combine automated headspace sampling with dual-detector gas chromatography, providing complete analysis of all key gases in a single automated run. These systems generate calibration curves using known gas standards and apply them to calculate the precise concentration of each gas in parts per million (ppm) in the original oil sample.

DGA Interpretation Methods

Raw gas concentration data alone is insufficient for transformer fault diagnosis. The data must be interpreted using established diagnostic methods that relate gas patterns to specific fault types. Several internationally recognized interpretation methods have been developed over decades of research and field experience.

Individual Gas Concentration Limits (IEEE Method)

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) developed a four-condition classification system based on total dissolved combustible gas (TDCG) concentration and individual key gas limits. This method is particularly useful when no historical DGA data exists for comparison.

- Condition 1 (TDCG < 720 ppm): The transformer is operating satisfactorily with normal gas levels. Routine annual or biannual sampling is sufficient.

- Condition 2 (TDCG 721-1,920 ppm): Higher than normal combustible gas levels are present. A fault may be developing. Quarterly sampling is recommended to establish gas generation rates.

- Condition 3 (TDCG 1,921-2,630 ppm): High combustible gas levels indicate a likely fault condition. Monthly sampling and close monitoring are required.

- Condition 4 (TDCG > 2,630 ppm or any individual gas exceeding critical limits): Continued operation may result in failure. Immediate investigation and possible removal from service are necessary.

This method also specifies critical concentration limits for individual gases. For example, hydrogen exceeding 1,800 ppm automatically places the transformer in Condition 4 regardless of TDCG, because such high hydrogen levels indicate severe partial discharge or arcing.

Rogers Ratio Method

The Rogers Ratio Method uses four calculated gas ratios to identify fault types. The ratios are:

- \(R1 = CH_4/H_2\) (methane to hydrogen ratio)

- \(R2 = C_2H_2/C_2H_4\) (acetylene to ethylene ratio)

- \(R3 = C_2H_2/CH_4\) (acetylene to methane ratio)

- \(R4 = C_2H_6/C_2H_2\) (ethane to acetylene ratio)

Each ratio is evaluated against defined ranges to classify the fault into categories such as normal aging, partial discharge, thermal fault (low, medium, or high temperature), or arcing. The Rogers method provides more detailed thermal fault classification than earlier ratio methods and has been widely adopted in North America.

IEC 60599 Basic Gas Ratio Method

The International Electrotechnical Commission standard IEC 60599 defines a three-ratio method similar to Rogers but with different ratio ranges and interpretations. This method uses:

- \(R1 = C_2H_2/C_2H_4\)

- \(R2 = CH_4/H_4\)

- \(R5 = C_2H_4/C_2H_6\)

The standard provides lookup tables that correlate specific ratio combinations with fault types including partial discharge (PD), discharge of low energy (D1), discharge of high energy (D2), thermal fault with temperature below 300°C (T1), thermal fault 300-700°C (T2), and thermal fault above 700°C (T3). IEC 60599 is the dominant standard in Europe, Asia, and many other regions.

Key Gas Method

The Key Gas Method takes a simpler approach by focusing on which gas or gases are present in the highest concentrations. Different fault types produce characteristic “fingerprint” patterns:

- Partial Discharge: Predominantly hydrogen with lower concentrations of methane and ethane

- Thermal Fault (Low Temperature): Methane and ethane dominate

- Thermal Fault (Medium Temperature): Ethylene becomes prominent along with methane

- Thermal Fault (High Temperature): High ethylene with significant methane and hydrogen

- Arcing: Acetylene is the key indicator, accompanied by hydrogen and ethylene

The Key Gas Method is particularly useful for quick preliminary diagnosis but should be confirmed with other methods for critical decisions.

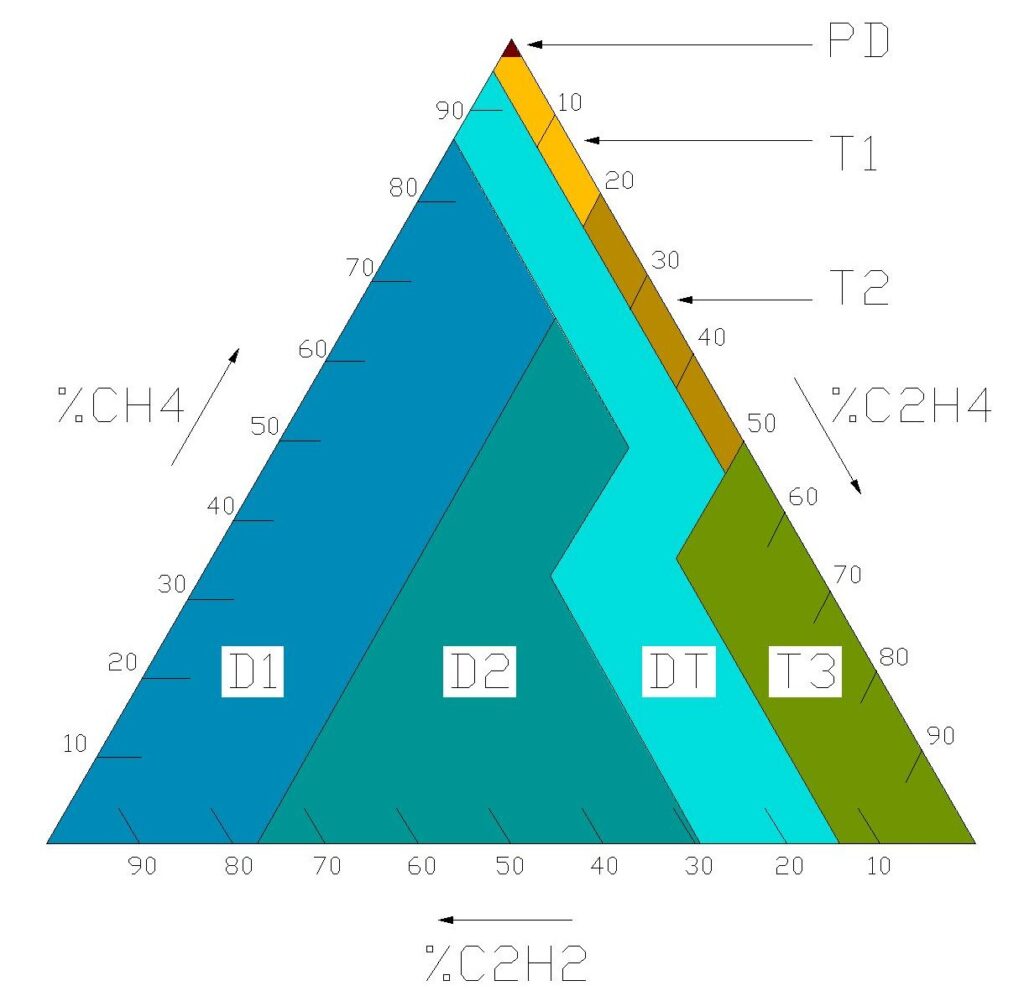

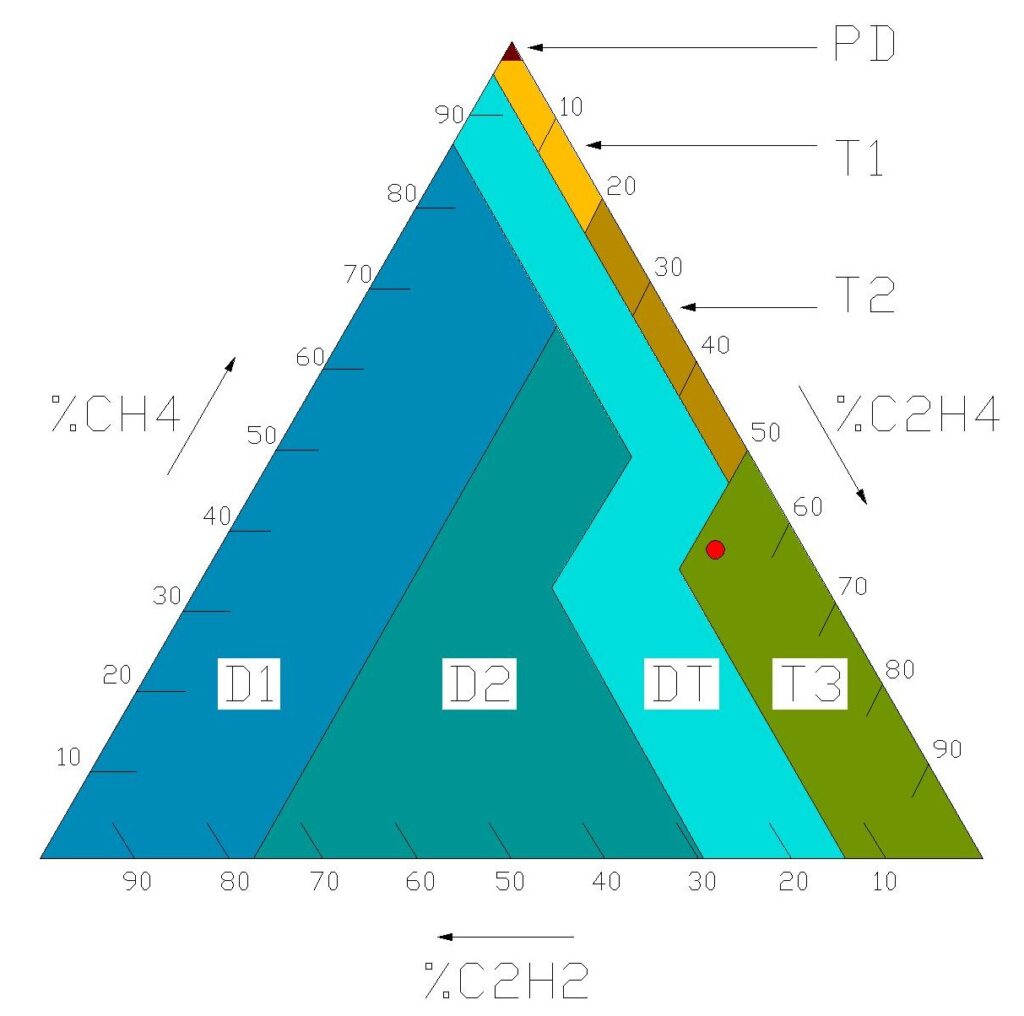

Duval Triangle Method

Developed by Michel Duval, the Duval Triangle provides a graphical interpretation method using only three hydrocarbon gases: methane \((CH_4)\), ethylene \((C_2H_4)\), and acetylene \((C_2H_2)\). This method has gained popularity due to its simplicity and high diagnostic accuracy.

The procedure involves calculating the relative percentages of the three gases as a proportion of their sum, then plotting the point on a triangular coordinate system:

- Calculate the sum: \(T = CH_4 + C_2H_4 + C_2H_2\)

- Express each gas as a percentage of \(T\):

- \(\%CH_4 = 100 × CH_4 / T\)

- \(\%C_2H_4 = 100 × C_2H_4 / T\)

- \(\%C_2H_2 = 100 × C_2H_2 / T\)

- Plot the point \(\%CH_4,\, \%C_2H_4,\, \%C_2H_2)\) on the Duval Triangle diagram

The triangle is divided into seven fault zones: PD (partial discharge), T1 (thermal fault <300°C), T2 (thermal fault 300-700°C), T3 (thermal fault >700°C), D1 (low-energy discharge), D2 (high-energy discharge), and DT (mixture of thermal and electrical faults). The location of the plotted point identifies the fault type.

For example, if the gas analysis shows CH₄ = 70 ppm, C₂H₄ = 110 ppm, and C₂H₂ = 20 ppm, the sum T = 200 ppm. The percentages are %CH₄ = 35%, %C₂H₄ = 55%, and %C₂H₂ = 10%. When plotted, this point falls in zone T3, indicating a high-temperature thermal fault.

The Duval Triangle method has been validated against thousands of transformer cases and shows excellent correlation with actual fault conditions.

Standards and Guidelines

DGA testing and interpretation are governed by several international and national standards that ensure consistency and reliability across the industry.

- ASTM D3612 specifies standard test methods for analysis of gases dissolved in electrical insulating oil by gas chromatography. It defines three acceptable extraction procedures: vacuum extraction (Method A and B), headspace sampling (Method C), and provides detailed requirements for analytical equipment, calibration, and quality control.

- ASTM D3613 covers the sampling of electrical insulating oil for dissolved gas analysis, specifying proper sampling containers, procedures, and handling requirements to maintain sample integrity.

- IEC 60599 provides comprehensive guidance on interpretation of dissolved and free gas analysis for mineral oil-filled electrical equipment in service. This widely adopted international standard describes gas formation mechanisms, fault identification methods including the basic gas ratio method, and recommended actions based on gas concentrations and generation rates.

- IEEE C57.104 (IEEE Guide for the Interpretation of Gases Generated in Mineral Oil-Immersed Transformers) offers detailed North American guidance on DGA interpretation, including the four-condition classification system, recommended sampling frequencies, and operational procedures based on gas levels and generation rates.

Limitations and Considerations

While DGA is an exceptionally powerful diagnostic tool, analysts must understand its limitations to avoid misinterpretation.

- Location Uncertainty: DGA cannot pinpoint the exact physical location of a fault within the transformer. It only indicates that a fault condition exists somewhere in the oil-filled active part.

- Fresh Oil Effect: If a transformer has been recently refilled or topped up with fresh oil, the dilution effect can mask or reduce gas concentrations, making results unreliable indicators of actual fault severity. Historical context and knowledge of oil additions are essential.

- Load Tap Changer Influence: On-load tap-changing transformers may show elevated levels of acetylene, hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide in the main tank oil due to gas migration from the tap changer compartment.

- Stray Gassing: Some transformer oils, particularly certain inhibited mineral oils, can produce methane and ethane under normal operating temperatures without any fault being present. This “stray gassing” behavior must be recognized to avoid false alarms.

- Multiple Faults: When multiple simultaneous faults exist, their gas signatures can overlap, making interpretation more complex. Different diagnostic methods may yield conflicting results in such cases.

- Trend Analysis Importance: A single DGA result provides limited information. The rate of change in gas concentrations over time (gas generation rate) is often more diagnostically valuable than absolute concentration levels. Regular periodic testing establishes baselines and reveals developing trends.

Relationship to Other Transformer Tests

DGA should be viewed as one component of a comprehensive transformer condition assessment program. It works synergistically with other diagnostic tests to provide a complete picture of transformer health.

When abnormal gas levels are detected, additional tests may be necessary to confirm findings and assess the severity of the condition. Tests such as the transformer winding resistance test can identify loose connections or broken conductor strands that might cause localized heating. The core insulation test evaluates insulation integrity between core laminations and ground, which is particularly important when DGA shows high levels of ethane, ethylene, or methane that could indicate core heating.

Other complementary tests include the sweep frequency response analysis (SFRA) which detects mechanical deformation of windings that might result from through-faults or transportation damage, and capacitance and tan delta testing of transformer windings which assesses the condition of the insulation system.

Routine electrical tests like the open circuit test and short circuit test help verify that the transformer’s electrical characteristics remain within acceptable limits. During commissioning of new transformers, a full suite of tests including the vector group test, polarity test, and magnetic balance test ensures proper configuration and operation.

Regular insulation resistance testing using a Megger and performing dielectric absorption index tests provide additional insight into the overall condition of the insulation system.

Sampling Frequency Recommendations

The frequency of DGA sampling should be based on the transformer’s criticality, age, loading, and previous test results.

For new transformers in their first year of service, baseline DGA samples should be taken shortly after commissioning and at 3-6 month intervals to establish normal operating characteristics.

Routine monitoring of critical transformers in normal service typically involves annual sampling as a minimum. For less critical or distribution transformers, biennial or triennial sampling may be acceptable.

When gas levels enter higher condition categories or show increasing trends, sampling frequency must increase. IEEE guidelines recommend monthly sampling when gas generation rates exceed 30 ppm/day, or quarterly sampling for rates between 10-30 ppm/day.

After any unusual event—such as through-faults, overloading, operation of protection devices, or suspicious noises—an immediate DGA sample should be taken to assess whether internal damage has occurred.

Transformers with known issues or those nearing end of life may require quarterly or even monthly monitoring to track condition changes and plan maintenance or replacement.

Conclusion

Dissolved Gas Analysis stands as the premier diagnostic technique for detecting incipient faults in oil-filled transformers before they progress to failures. By analyzing the types, concentrations, and generation rates of gases dissolved in transformer oil, maintenance engineers gain invaluable insight into internal conditions that would otherwise remain hidden until catastrophic failure occurs.